Colorado Employment Growth Deteriorated at a Rapid Pace in the First Quarter, Let’s Talk About That

Exploring the significance in Colorado losing private sector jobs on an over-the-year basis in March and what it could mean for the state going forward

Note: due to the length of this article, it may truncate when received via email. Visit this link if you run into those issues: https://ryangedney.substack.com/archive.

Introduction

With so many different options available to track labor market trends, it’s understandable that data from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) could be overlooked. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the QCEW “is a quarterly count of employment and wages reported by employers [… that] covers more than 95 percent of U.S. jobs available at the county, Metropolitan Statistical Area, state, and national level, by detailed industry.” Additionally, “the primary source for the QCEW is administrative data from state unemployment insurance (UI) programs [… that] BLS and state workforce agencies review and enhance” prior to publication. In other words, QCEW is a product of employment and wage data that employers report to state UI divisions as a required function of their quarterly filings, which is then turned into a usable economic series after thorough review by state Labor Market Information (LMI) offices and BLS staff. Due to QCEW’s vast coverage of jobs (and designation as a census), it also serves a crucial role for other BLS and LMI programs as a source for adjusting sample-based employment estimates during annual benchmark revisions.

Well, This Doesn’t Look Good

As a standalone resource, though, one reason QCEW data may go unnoticed stems from publication lag. Because of its relationship with the UI employer filing process, the QCEW operates on a 5-7 month delay between the newest information available and the timing of that release (for instance, QCEW employment data for January, February, and March 2024 was published on the BLS website on September 4th). However, this most recent batch of QCEW data revealed something extremely noteworthy and alarming for Colorado – the state lost private sector jobs in March compared to the year prior. This article will explore the significance of Colorado’s recent job loss, possible drivers for the rapid deterioration of employment growth in the first quarter of 2024, and what it could mean for the state going forward.

Per QCEW estimates, employment in Colorado’s private sector declined by 0.3% in March on an over-the-year basis. This represented a drastic change compared to just four months prior (November 2023), when private industry jobs grew at a rate of 2.0%. When measured against other states, Colorado’s private job growth rate of -0.3% ranked 47th, and was substantially lower than the U.S., which increased by 1.0% in March. As demonstrated in the following two charts, Colorado’s recent downward shift in employment growth puts the state in its worst position relative to the U.S. and other states in over 20 years.

We’ve Seen This Story Before

Something that might have been obvious when reviewing the national rank chart is that the other two periods to feature a Colorado job growth ranking of 45th or worst coincided with U.S. downturns: the early 2000s recession and the Great Recession. To highlight the similarities between those two recessions and early 2024, the next chart displays the over-the-year percentage change in Colorado’s private sector for a select number of months during 2001-02, 2008-09, and 2023-24. The anchor month (referenced as M0) represents the first time Colorado’s private sector growth rates turns from positive to negative during each period (August 2001, September 2008, and March 2024, respectively). To the left of M0 (referenced as M-1 to M-7) work back to how many months passed between the state having a private sector growth rate of at least +2%, prior to the switch to negative (four months for both 2001 and 2024 and seven months for 2008). The rest of the chart (referenced as M+1 to M+9) shows Colorado’s private sector growth rates 1 to 9 months after M0 (blue line = 2001-02 and orange line = 2008-09). The accelerating decline in the 2001-02 and 2008-09 growth rates following M0 is instructive for a potential 2024 outlook, given how Colorado’s recent deterioration in private sector job growth mirrors the start of the 2001 and 2008 recessions. After only five months following the turn to negative, the state’s private sector job growth rate was -4.1% in both the 2001-02 and 2008-09 periods (this time lapse is equivalent to the shift from March 2024 to August 2024). For the remaining four months (M+6 to M+9, or comparable to September-December 2024) there’s a clear divergence between the severities of the two periods, with the growth rate approaching -7% midway through 2009, compared to a decline ranging between -3% and -4% in early 2002.

Using this information can help to forecast a potential annual average growth rate for Colorado’s private sector in 2024 if the state continues to replicate the change in jobs observed during the 2001 and 2008 recessions. An annual average growth rate ranging between -2.3% and -3.0% is estimated for the state’s private sector in 2024 when taking the known growth rates for the first three months of 2024 (+0.6%, +0.2%, and -0.3%, respectively) and forecasting the remaining nine months based on varying assumptions informed by the 2001-02 and 2008-09 changes in employment. That annualized growth rate of -2.3% to -3.0% would be equivalent to Colorado shedding an average of 56,000 to 73,000 private jobs between 2023 and 2024, plunging the state deep into a recession.

While the first three graphics have focused on the top-line employment changes for Colorado’s private sector, it’s also valuable to assess these shifts at the industry level. There are 19 industry sectors that contain private employment (by definition, government/public sector, is excluded). The table below shows a wide range of private sector job data for these industries, including: March 2023 employment levels, March 2024 employment levels, March 2024 over-the-year growth rate, the national ranking of the March 2024 growth rate, and an indicator of whether the industry sector experienced job loss.

What is abundantly clear in the table above is that the distribution in employment loss is widespread throughout the industries. A total of nine industry sectors (or 47%) lost jobs in March compared to the year prior, with growth rates ranging from flat (finance and insurance) to a decline exceeding -5% (information). Additionally, employment in a key Colorado industry (professional, scientific, and technical services) decreased by 1.3% in March, the largest over-the-year drop for that sector since mid-2010 (yes, even bigger than during the pandemic). As mentioned previously, Colorado’s private sector employment growth ranked 47th nationally in March, which is not surprising when this table reveals 10 industry sectors within the state with ranks of 40th or worse. Notably, some of Colorado’s worst sector ranks belong to industries that had job gains in March (arts, entertainment, and recreation: 47th and health care and social assistance: 48th).

So how does this distribution of Colorado industry sectors experiencing over-the-year declines in private employment compare to previous years? Based on the subsequent visual, the current allocation of 47% of sectors with job loss lines up with the 2001 and 2008 recessions (the 2020 pandemic is not noted in this comparison due to its unique status as a recession driven by a health crisis and the need to shut down the entire economy in April of that year).

Given that the recent rapid deterioration in Colorado’s private sector employment follows more closely to the beginning of the 2001 recession (ex. speed of shift from +2% growth to negative growth, share of sectors with job loss, and impact to the broader tech industry), it’s a worthwhile exercise to attempt to estimate the state’s 2024 unemployment rates using that early 2000s downturn as a baseline. Colorado’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate moved up from 3.1% in April 2001 to 4.0% in August 2001 (an increase of 29%), which matches the months when the state’s private sector job growth rate shifted from at least 2% to negative. Five months later (January 2002), the unemployment rate had ballooned to 5.7% (a gain of 84% compared to April 2001). When these changes are applied to Colorado’s November 2023 unemployment rate of 3.3%, a drastically different picture for the state is presented than what the current figures show.

As the chart below highlights, Colorado’s estimated unemployment rate rises to 4.3% in March 2024 and to 6.1% by August. The state’s unemployment rate exceeding 6.0% would represent a meaningful and significant change compared to the August rate of 4.0% published last week. An August 2024 unemployment rate of 6.1% would translate to 198,000 unemployed Coloradans, compared to the current estimate of about 128,000 individuals.

There’s no way to sugarcoat it, these recent employment trends from the QCEW paint an extremely grim and dire situation for Colorado, one in which the state is highlighted as a national leader for recessionary activity.

Additionally, due to QCEW’s status as a source for adjusting sample-based employment estimates during annual benchmarking, these data will be incorporated into the revised Current Employment Statistics (CES) and Local Area Unemployment Statistics (LAUS) numbers when the new information is released next March. CES, which has post-benchmark growth rates that are highly correlated with QCEW (ex. from 2001 to 2022 the R2 for Colorado’s QCEW and CES not-seasonally-adjusted private employment growth rates is 0.9994), will be substantially impacted. Due to definitional and methodological differences, LAUS employment estimates may not shift as much as QCEW trends would indicate, but the two series are still meaningfully correlated after benchmark (ex. the R2 for Colorado’s LAUS not-seasonally-adjusted employment and total QCEW growth rates is 0.8341). The March 2024 QCEW figures were also the driver for determining how the national and state- level preliminary benchmark revision estimates were derived. Those preliminary estimates, which were released on August 21st, received some media attention in Colorado due to the state having the largest downward estimates in the nation, both in absolute and percentage terms.

Now, this article could end on these foreboding points, but there are some inconsistencies in this economic story that need to be discussed. The remainder of this analysis will dig into these incongruities and look beyond just taking the recent QCEW data at face value.

Labor Market Inconsistencies

The Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) provides many helpful labor market statistics at the national and state level. This survey-based program collects data from employers on characteristics like job openings, hires, and separations. The next chart shows Colorado’s hires and openings as a share of total nonfarm employment since 2001. Of particular importance is the openings rate (purple line), which dipped to around 3% at the start of the 2001 and 2008 recessions, but remains at a historically high level (above 6%) in 2024. While the recent openings rate has declined from the early 2023 all-time peak of over 8%, it is still well above pre-pandemic levels. The hires rate (green line), which doesn’t historically exhibit identifiable countercyclical trends like the openings rate, is more or less hovering around the long-run average of 4.3% based on the most recent data available (three-month period ending July 2024). Combined, these datasets lack movement that would one would expect following, or coinciding with, a recent period of swiftly decreasing private sector employment.

While the majority of labor market data are either coincident or lagging indicators, initial claims for unemployment insurance (UI) are typically viewed as a leading indicator. An initial claim is filed by an individual to initiate the UI benefits process, but does not automatically guarantee payment. However, initial claims historically serve as a reasonable proxy for layoff activity. Colorado initial claims, which are essentially reported in real-time and rarely revised, rose steeply at the onset of the 2001 and 2008 recessions. In total, weekly claims filed between Q3 2001 and Q1 2002 swelled by 67.1% compared to the same period one year prior. The change was even more prominent in the early stages of the Great Recession, when claims grew by 84.0%. That said, the number of weekly initial claims tabulated within the first nine months of 2024 have increased by only 13.5% relative to the total number registered between January 2023 and September 2023. This trend runs counter to what one would expect following, or coinciding with, a recent period of swiftly decreasing private sector employment.

The Unforeseen Consequence of Modernization

In this article’s introduction, it was mentioned that the QCEW is reliant on employment and wage data that employers are required to report to UI offices as part of their quarterly filing. Over a multiple year period, the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment embarked on an overdue project to update and modernize its 40-year-old unemployment insurance system. This well-publicized endeavor was completed in two waves: the benefits portion of the new system, which is used to process unemployment claims, went live at the beginning of 2021, while the premiums component of the new system, which is utilized to process employer quarterly payments and wage reports, became active in October 2023. Due to deadlines that stipulate when employers are required to submit their quarterly reports, employment and wage data for the third quarter of 2023 represented the first time that Colorado’s UI division used the new system to process that information (therefore, data for Q2 2023 and before relied on the old system). The next portion of this analysis will detail some concerning and bizarre data trends that happened to coincide with the implementation of the new premiums system.

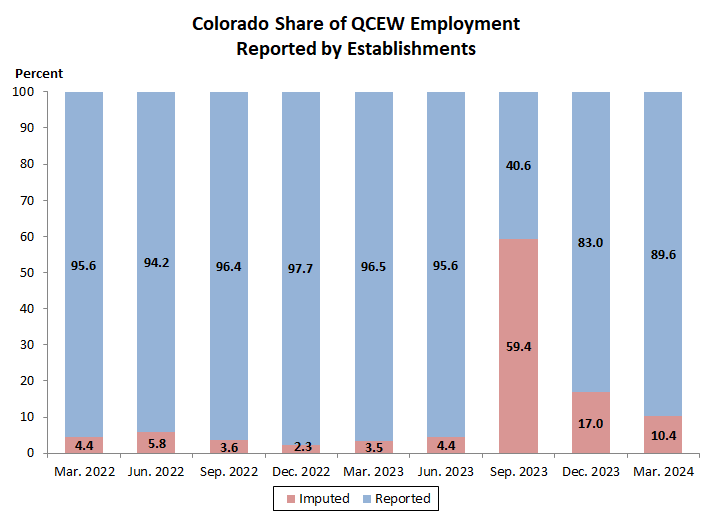

A little known byproduct of the QCEW publication cycle is a report the BLS makes publicly available that tracks quarterly QCEW reporting rates. Essentially, this resource looks at the share of quarterly QCEW establishment, employment, or wage data that were actually reported by employers to UI and did not receive any corrections or adjustments by the state QCEW program or the BLS during the processing period prior to publication. As noted by the BLS, “reporting rates are generally very high because employers are required to file reports under the UI law for each state…more than 90 percent of establishments at the national level typically report their data each quarter, accounting for upwards of 95 percent of employment and wages.” These levels have more or less historically held for Colorado, until Q3 2023, when the state’s reporting rate for QCEW establishments plummeted to 28.3%. While those establishment rates rebounded to around 85% in the following two quarters, it’s hard to ignore the timing between the sudden decrease and the shift to a new UI premiums system.

Of potentially greater importance is the employment reporting rate, which looks at the share of QCEW employment reported by establishments. Similar to the establishment rate, the reporting share for employment declined sharply in Q3 2023 to 40.6%, which is presented in the chart below (rates for the last month of each quarter shown). Subsequent quarters displayed relative improvement, but still have adjustment (aka imputed) shares more than twice as high as the average prior to modernization of the UI premiums system (4%). To put that comparison into context, consider that, per QCEW, Colorado’s total employment level (public and private sectors) in March 2024 was 2.851 million. If you take that figure and multiply it by the pre-modernization average employment imputation rate of 4%, you end up with approximately 114,000 in employment that was corrected. Conversely, following the same approach and utilizing the March 2024 imputation rate of 10.4% yields nearly 300,000 in employment that was adjusted. That introduces a lot more volatility and uncertainty into the QCEW estimates, which could be meaningful when observing whether the state adds employment over the year or loses jobs. Between Q1 2022 and Q1 2024, there have only been nine instances where a state or U.S. territory had a QCEW employment reporting share under 90%. Colorado owns three of those occurrences, all taking place after Q2 2023.

The link between QCEW and annual benchmarking for the Current Employment Statistics (CES) program has been highlighted multiple times throughout this article. Due to the timing of the state-level benchmark process (and subsequent publication), third quarter QCEW data is the most recent available to be incorporated into the annual CES adjustments. Historically, this is a neat-to-know fact for those not actively involved in this process, but was of notable significance for the most recent benchmarking cycle. Within this year’s annual CES State and Area Benchmark Article (published in mid-March), the BLS added a special note regarding Colorado’s employment data. The notice stated that “the preliminary version of third-quarter 2023 QCEW Colorado data available at the deadline for establishing the CES benchmark levels showed unusual movements […and that] these unusual movements were likely due to the modernization of the Colorado unemployment insurance premiums system.” The rest of the note goes on to say that while “administrative data derived from QCEW” between April 2022 and June 2023 were utilized as part of the benchmarking process, the “BLS calculated employment levels for July 2023 through September 2023” using an estimation procedure. In other words, Q3 2023 QCEW data were excluded from the CES benchmark due to concerns with the quality of that information.

One useful, but underutilized, offshoot of the QCEW is a suite of datasets produced by the BLS called Business Employment Dynamics, which is available for all states and the nation. This program takes establishment-level data from the QCEW and generates quarterly statistics like gross job gains and losses, business births and deaths, and changes in employment due to openings, closures, expansions, and contractions. The following panel highlights four of these data series for Colorado, which goes back to 1992. The upper left corner captures the number of Colorado establishments with gross job gains, while to the right of that are the number of establishments with employment gained by expansions. Along the bottom row are displayed the number of Colorado establishments with employment lost by either contractions or closings. Identified within each chart are data points that correspond with four periods: Q2 2020 (start of the pandemic and closure of the economy), Q3 2020 (some re-opening of the economy), Q3 2023 (first quarter under the new UI premiums system), and Q4 2023 (second quarter under the new UI premiums system). What becomes instantly evident when reviewing these charts is the level of volatility in the Q3 and Q4 2023 data, which either matches or exceeds movement observed during the height of the pandemic. In one instance (Colorado establishments with employment gained by expansions), the Q3 2023 level reached the lowest point in the history of the series, while in another (employment lost by closings), the Q4 2023 level surged by more than double compared to the prior quarter. While the 2020 swings are easily explainable by economic circumstances, the volatility in the aggregated establishment-level data during the second half of 2023 appears to be driven by administrative factors.

The final concerning/bizarre data trend brings us back to the QCEW industry sector table presented earlier that showed Colorado’s national ranking in the over-the-year change in private employment. This new table, however, includes March 2019 and June 2023 rankings in addition to the March 2024 ranks. March 2019 simply reflects a pre-pandemic period, while June 2023 represents the last month of QCEW data available prior to the shift to the new UI premiums system. In March 2019, Colorado had the 11th best private sector growth rate. This advantage clearly eroded over the following four years, as the June 2023 ranking fell to 31st. Additionally, there was only one industry sector in March 2019 with a ranking of 40th or worst (accommodation and food services), while there were a total of six with similarly lackluster ranks in June 2023. From this perspective, Colorado’s job market was cooling relative to other states. As previously discussed, that temperature turned ice cold in the nine months that passed between June 2023 and March 2024. But upon further inspection, some of industry-level shifts in rankings over that period that seem to exceed a reasonable threshold. Specifically, the table below highlights (in yellow) six sectors that experienced an absolute change of 20 or more in ranking in March 2024 compared to June 2023. With the exception of finance and insurance, worsening ranks occurred for these selected industries. While it’s not impossible that logical explanations exist to support the broad-based and rapid deterioration of Colorado’s employment growth, the inconsistencies detailed above obscure the ability to confidently assess the state’s labor market.

Closing Thoughts

Frankly, the main points presented in this article places Colorado into a lose-lose situation. If the recent QCEW data is taken at face value, then the state is likely already headfirst into a recession. On the other hand, a deeper look at the information generated by QCEW implies there are several issues with data quality, which will have widespread impact on crucial labor market series and further complicate a currently murky viewing of Colorado’s economic outlook.

This influence of uncertainty is already being felt within Colorado, as observed by language provided within last week’s September 2024 state economic and revenue forecast documents produced by the Office of State Planning and Budgeting (OSPB) and Legislative Council staff, respectively. Per the OSPB (page 10 of their outlook), “This August, the BLS announced that the existing published survey data is likely overcounting jobs growth by a more significant margin than usual in both the U.S. and Colorado…in Colorado the loss is much higher [than the U.S.]…OSPB is in conversations with the relevant state and national agencies to get a better grasp on causes, but if this data holds through next March, it would indicate approximately flat jobs growth in the state in 2024.” Additionally, the Legislative Council staff forecast (page 61) highlights several concerns: “Larger than usual expected revisions, reduced household and establishment survey response rates since the pandemic, and a system modernization that disrupted the collection of employment census data in Colorado at the end of 2023 combine to make the state employment picture cloudier than usual.”

While it may seem that these labor market data are only meaningful to economists and analysts, they play a crucial role in our society. However, the value of this data relies on the quality and standards of that information. Second quarter 2024 QCEW data for Colorado is scheduled to be released on November 20th, while the BLS will release full statistics for all states on December 5th – it’s recommended that those data releases are not overlooked.